Created by Bob Hayes, Managing Editor; Kathleen Kotwica, Ph.D., EVP and Chief Knowledge Strategist; and Richard Lefler, Emeritus Faculty, Security Executive Council

An edited version of the following appeared in Financial Executive magazine. This content cannot be copied or distributed without written permission from The Security Executive Council.

Malicious insiders can and do perpetrate sabotage; fraud; monetary, asset, and data theft; and critical information leaks that can be far more damaging to the organization than any external attack. Financial executives may not feel directly responsible for managing malicious insider activity, but they are uniquely positioned to help detect, prevent and respond to much of it.

The insider threat should be a significant concern for both public and private organizations. Julian Assange's release of sensitive information leaked by insiders from both corporations and the government through WikiLeaks is only one example. Others have carried a daunting price tag.

- In 2009, three workers at a Domino's restaurant in Conover, N.C., shot a video of themselves doing unsavory things to pizzas slated for delivery by workers, which was later uploaded to YouTube. After the video went viral, Advertising Age reported a toll on Domino's quality and buzz ratings as measured by BrandIndex. Buzz fell from 22.5 points to 13.6 points. Quality ratings fell from 5 to minus 2.8. Zeta Interactive's measurements show Domino's buzz rating had been overwhelmingly positive, at about 81 percent. After the video's release, perception became 64 percent negative. Estimates of Domino's loss of brand value were between $3 billion and $4 billion, and the company's stock took a hit.

- An employee of Microsoft was sentenced to 22 months in prison for embezzling nearly $1 million by inflating expense reports for Internet domain names that she bought and maintained for the company using her corporate credit card.

- A former director of Long Island University's Hillwood Museum was sentenced to 12 months in prison for stealing Egyptian artifacts from the institution's collection. He had deleted files concerning the nine objects from the museum's computer database, then removed them and delivered them to Christie's for auction, where eight of them sold for a net $51,500. He eventually confessed, saying his motivation for the theft was to exact revenge against the university for his perceived mistreatment while an employee there.

- An employee at DuPont was planning to smuggle trade secrets to China by downloading confidential company files from his company-issued laptop to an external hard drive. DuPont was hit by a similar incident just a few years before when an employee accessed more than 16,700 documents and more than 22,000 scientific abstracts with the intention of giving them to a DuPont rival. In that case, the documents included information on all DuPont's major product lines as well as emerging technologies; prosecutors later valued the information at $400 million.

- Network administrator for the city of San Francisco Terry Childs locked administrators out of the city's computer network after allegedly being disciplined for poor performance. The network handled city payroll files, jail bookings, law enforcement documents and official e-mail for the city. City officials told the San Francisco Chronicle that Childs may have caused millions in damage while also rigging the network so that other third parties could monitor traffic, posing a huge data security risk.

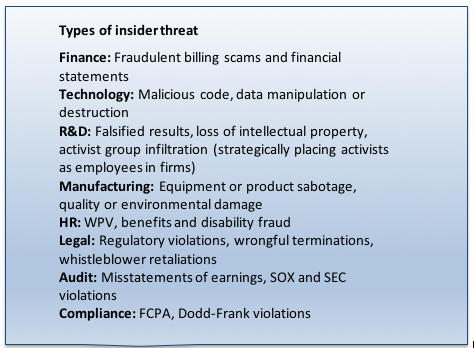

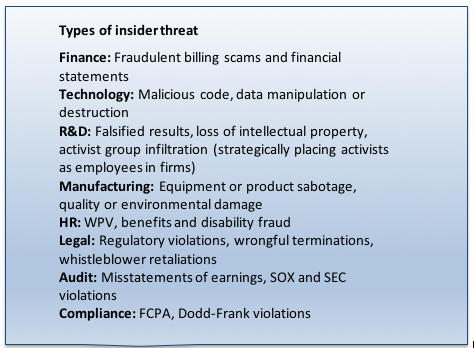

As these examples indicate, malicious insiders may use a variety of methods to cause damage - network or manual sabotage, espionage, fraud, embezzlement, misuse of information or theft of intellectual property carried out by electronic means or on paper. (And with the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, we can't neglect the potential for employees to seek or plant evidence of wrongdoing in order to profit from the 10 to 30 percent of monetary sanctions granted to whistleblowers under the law.)

They may act alone or with the support of an outside party such as an organized cyber crime group or a state-sponsored entity. The malicious insider can come from any function in the organization, and from any level, from third-party contractor to staff to executive. They may want to hurt the company for revenge, or as a strategy for advancement, or they may simply be looking for a way to skim off some cash.

Are these concerns unfounded or blown out of proportion? Many senior executives believe insider threat is a low-frequency event; however, malicious insider data leaks were up by over 50% in the first six months of 2009, according to KPMG's 2009 Data Loss Barometer research. And the cost of significant insider events is undeniably high. The 2010 Cybersecurity (e-crime) Watch Survey (conducted by CSO, the U.S. Secret Service, CERT and Deloitte's Center for Security & Privacy Solutions) and Ponemon Institute's Cost of Cyber Crime Study 2010 find that insider incidents are often more costly than external breaches. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners' 2010 Report to the Nations estimates that the typical organization loses 5% of its annual revenue to fraud. When applied to the estimated 2009 Gross World Product, that figure translates to a total of more than $2.9 trillion. And those statistics only account for two types of malicious insider activity.

Recent research by the Security Executive Council shows that while security leadership ranks insider threat as a high-level concern, they don't feel senior management always agrees. Clearly organizational risk is a C-level issue (Warren Buffett was even quoted in Fortune in 2008 as saying "The CEO has to be the chief risk officer"), but the insider as a perpetrator may not specifically show up on the radar. We argue that all senior management should be aware of and watching for this issue, and that the financial executive should be particularly on guard.

First, the CFO is in a good position to clearly define the organization's valuable assets, which is the first step to adequate protection against any threat. Second, functions that are critical in early detection and prevention of insider attacks, including accounts payable, information, the comptroller, accounts receivable and purchasing and supply chain, often report to the CFO. This gives the financial executive a unique perch to oversee these functions with an eye for the insider threat. If the CFO is attuned to this issue and watching those areas, he or she will greatly increase the odds that the company will discover malicious insider activity before it's too late.

The organization that employs enterprise risk management will enjoy a higher level of protection, particularly if the financial executive is a major team player in consideration of the insider threat. In a truly unified organization there should be many groups involved in risk oversight, including Business Conduct & Ethics, Compliance, Legal, Privacy, Audit, and Corporate Security. Each of them likely owns or monitors some function that can provide detection or prevention of malicious insider activity.

One might wonder whether insider risk truly needs to be managed separately from overall organizational risk. It needn't be managed separately, but it must be recognized as a unique risk category. Many financial executives have been involved in the ERM process and are very active in identifying risk to the organization, but little time is spent thinking about who the perpetrator is. Mitigating the insider risk involves a specific set of strategies because of the nature of the perpetrator.

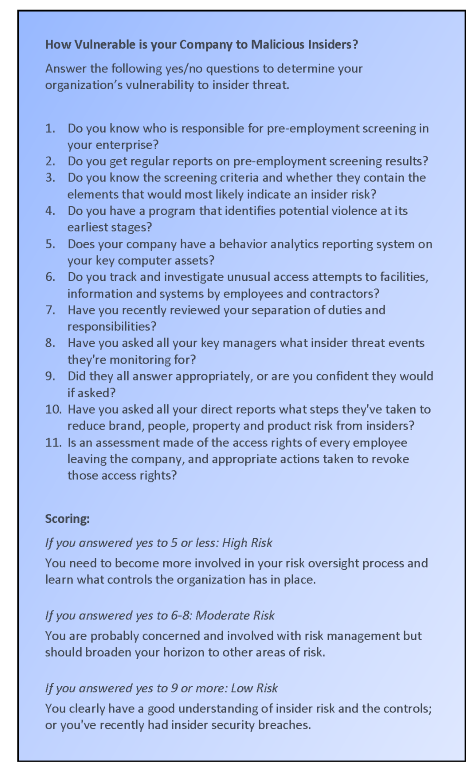

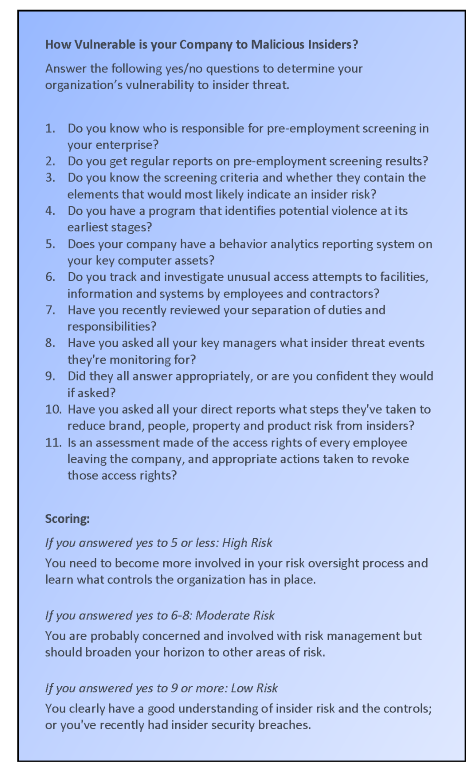

There are four types of mitigation strategies that may be employed to minimize insider risk:

- Keeping potentially malicious individuals out of the company (through comprehensive background screening, careful outsourcing, developing contractual language to require due diligence of contractors)

- Maintaining baseline security measures (including strong access controls over facilities, assets and information, compartmentalizing processes, separation of duties, fostering an ethical workplace)

- Encouraging awareness and reporting through formal measures (including regular training, anonymous tip hotlines, clearly communicated supervisor reporting procedures, and protections against retaliation)

- Detecting attempts early (through security incident and event monitoring tools and regular auditing of functions and processes)

Through unified oversight of risk and an internal focus on detecting insider threats, the financial executive can help the organization avoid significant brand and bottom-line damage.