By the Security Executive Council

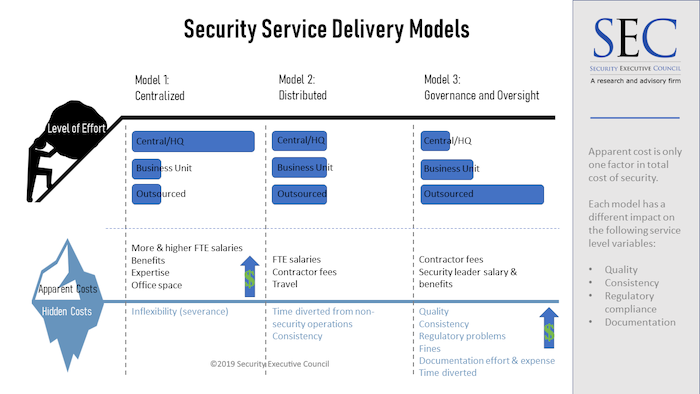

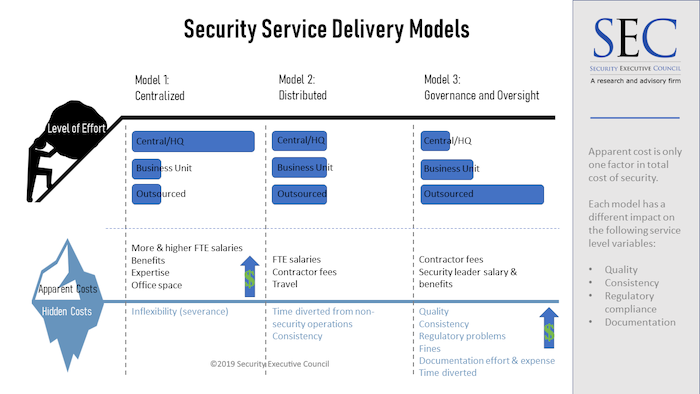

There are three primary models of security service delivery in organizations: centralized, distributed, and governance & oversight (primarily outsourced). Executive management may choose or propose one of these models on the basis of cost, but the apparent costs of any of these models are not the only costs to keep in mind. Each has hidden costs that will impact the total cost of security of that model. (

Click here for more information about how to define the Total Cost of Security.)

Which of these models most resembles your own program?

Model 1: Centralized

In this model, security resides primarily in-house, with a large central staff and a security leader over it. This centralized function writes guidance documents and process guidance for business units and other sites, as well as for a fairly small number of security-related contractors, and helps these units and sites handle the day to day requirements as necessary. In this model, in-house security does most of the work.

Pros: Because in this model you have security experts running security, they tend to do the work quickly and well, with quality and regulatory requirements in mind. They are able to leverage security-specific experience to avoid setbacks and implementation problems.

Cons: Because the centralized model requires a higher number of full-time employees, it also incurs a high cost in salaries and benefits, and it can be slow to change.

Model 2: Distributed

The distributed model has responsibility spread out among central corporate security, business units and contractors. In some instances, the business units report to their local leadership with a dotted line to the CSO, and in others they report directly to corporate security. In this model the site or business unit's effort tends to roughly equal the effort of corporate security, but the exact distribution will vary from organization to organization.

Pros/Cons: The pros and cons here may mirror those of the other two models, depending on the exact distribution between the three responsible entities. In the distributed model it's possible that organizations can leverage more of the pros of the other two models while mitigating some of the cons.

Model 3: Governance & Oversight

The SEC started seeing more of this model around ten years ago. In it, security offers many of the same services as Model 1, but hires contractors to execute under the oversight of, often, a single in-house security leader. It's what we call an "army of one" model. The security leader primarily writes policy, chooses vendors, and writes contracts. Managers and staff at the sites – who serve other functions and for whom security is only a small part of their overall responsibilities - shoulder more responsibility for security implementation than in Model 1, but the bulk of the effort lies with contractors.

Pros: This model is nimble and flexible and requires little commitment in terms of employees.

Cons: Model 3 tends to suffer in quality of service and consistency. While it may appear to cost less in terms of long-term staff cost, it tends to bring costly regulatory problems and expensive documentation effort. Because the program is being carried out by contractors and internal personnel with little security training or expertise, model 3 is likely to incur more fines, more time and expense to clear up mistakes in implementation, and more time to complete jobs.

Why is this important to know?

- If you're interviewing for a position, knowing the prospective company's service delivery model will help you understand whether this is the job for you.

Many security professionals go into new opportunities with the centralized model in mind. The model isn't discussed during the interview process, so they are shocked when they get into the position to find that management wants an army of one. Sometimes this realization only comes when the new leader begins trying to get new hires approved and to make larger changes.

In these cases, companies are sometimes hiring the wrong skills for the job. The main function of the position in the army of one is to write policy, guidance and contracts, not to manage staff or implement solutions.

If this information isn't clear during the hiring process, new hires don't negotiate budget money to minimize the variable and quality problems inherent in this model.

- If you're in a position and having trouble implementing your program, it's important to examine your organization and see if this is part of the problem.

You may think this should be apparent, but many never connect that the model in their mind isn't in line with the business model. It frequently isn't discussed inside or outside the organization. Security leaders simply believe they're doing a bad job because they're not getting buy-in or they're not getting what they need or what they ask for.

The biggest lesson here: Understand the business and align with it. The security leader must understand the business strategy rather than making assumptions about what it may be, including what service delivery model the business requires.